The Extremist Filter

How Britain’s electoral system has shielded us from extremism, and why that shield could one day entrench it.

Getting into the House of Commons is a tough gig. Just ask the SDP, UKIP, the Greens, the Brexit Party…. So the list goes on.

Consequently, Britain has never had an extremist government. The political landscape of Britain tends to flow slowly from one point to another over the cycle of decades (about every 30 years by my historical knowledge). We have never been a nation to fall foul of Continental excess in the political arena. This stability is essentially by construction. First past the post has traditionally prevented fringe groups from gaining momentum and becoming mainstream parties, unlike in some PR systems around the world. Our tranquil little island built itself a bastion against the far right and far left and thus far it has stood the test of time.

That’s because FPTP essentially acts like a filter. In my typical physicist style, I think of it a bit like an LED — they require a minimum amount of current to turn them on. And so, in political battle, parties require a large enough amount of support to tip the balance and win a few seats in parliament. Without that national coverage parties struggle to gain more traction and thus more seats, hence to make it parties need a mix of luck, popular appeal and local know-how. Miss any of these and your party is doomed to failure.

History backs this point up. During the 1930s, a wave of fascism swept across Europe and precipitated the Second World War. In Britain, we suffered through Mosley’s blackshirts, a group who were somewhat popular (famously having an office in Durham that is now a pizza shop) with 30,000 people attending a rally for the BUF in 1939. Despite this, the party never won a by-election or any seats in parliament — other than the one Mosley already held.

Skipping forward to the 1970s, the same story plays out. The National Front became a force in British politics, reaching their zenith in the mid-1970s winning 16% in the 1973 West-Bromwich by-election and won around 3.2% in the following general election. These are small numbers, but in an era defined by the two-party state these were remarkable figures for an upstart group. Yet, this group of neo-nazi fascists never won a seat or any major national power. The BNP saw a similar set of results in the early 2000s. Despite national appeal and conversations about these groups, neither were mainstream enough to overcome the FPTP barrier thus dooming their endeavours to failure.

More recent events show the same pattern. UKIP won 15% of the vote in the 2015 general election, yet only secured one seat in the House of Commons and then in 2024 Reform UK won 14% of the vote, picking up only five seats. FPTP presented an extreme barrier for these parties to overcome, essentially filter out views that did not align with the mainstream and hence throttling and major national representation — though as we shall see Reform UK are breaking that mould.

The common thread here is not simply that these movements lost steam, but that the electoral system itself cut them off at the knees. Under proportional systems, vote shares of 10–15% almost always translate into a sizeable bloc in parliament, giving fringe parties a foothold and a national platform. Britain’s first-past-the-post rules deny that translation. Unless support is geographically concentrated, even double-digit national vote shares can yield nothing more than a token presence at Westminster. It is this structural barrier, not just the fickleness of public opinion, that has kept extremists on the margins of British politics.

As with the LED analogy earlier, the filter blocks parties without concentrated support filtering out potentially extremist parties. They must gain enough votes to pass this filter before they become a dominant party. Before they become a dominant party they have to breakthrough at the national level, and hence they have to persuade a few seats to vote them in to parliament. This is essentially why the Liberal Democrats win so many seats with little vote share now and then — they focus that vote in a handful of seats. This gets them over the local hurdle giving them national presence.

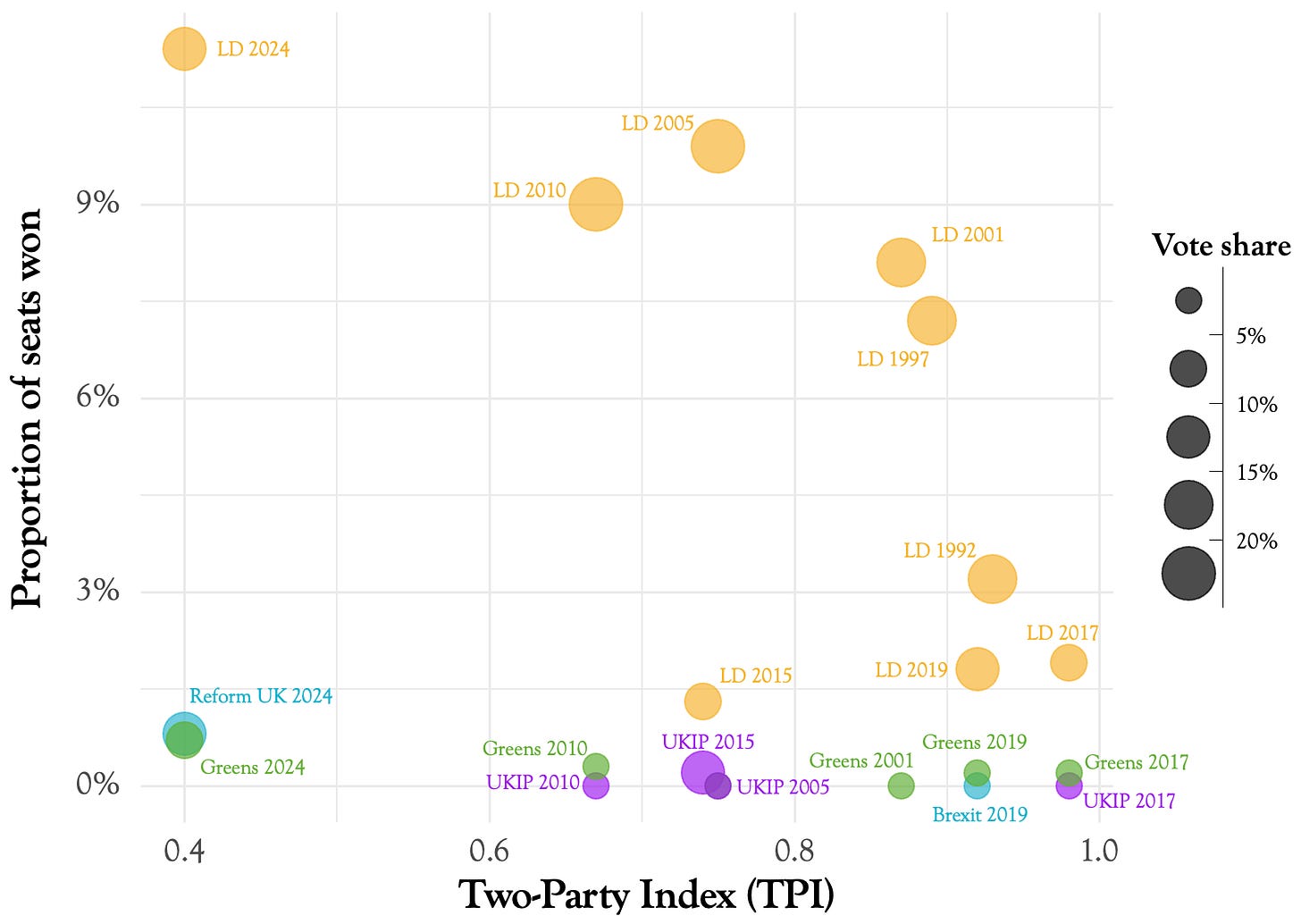

Quantifying this is a little tricky — pinning down the exact national vote share threshold is hard as I discovered on my train journey. But the graphic below give you an idea. The Two Party Index is a function I defined here and tells us how close Britain is to a two-party state. The filter is essentially a function of this, with larger TPIs leading to large barriers to entry. For example, in 2024 the barrier was very low and thus three smaller parties managed to pick up seats, whereas in 2017 the barrier was very high and hence the Liberal Democrats and Greens did worse.

FPTP also exacerbates vote psychology whereby voters worry about wasting votes and hence they often give them to parties that are more popular and hence are able to win. This prevents them from being governed by a party they dislike, for example tactical voting was used to devastating effect in the 2024 general election, with Labour’s swing curve being exceptionally efficient (something I wrote about here). This means that even popular parties can struggle to turn popular sentiment into seats if psychology is gamed.

The contrast with PR systems is stark. PR can allow extremist parties into parliament, giving them a voice that can amplify their message to much wider audience gaining them more traction. The AfD in Germany is a crucial example of this, moving the fringes to the mainstream in just a few years due to the voice PR offers them.

FPTP does have one fatal flaw. It is a bastion against extremism until the extremists sneak in, then that bastion protects them and they become the mainstream.

As Marta Lorimer argues, the two-party system can give a misleading veneer of unity: ‘the two-party system has never been the only game in town’, suggesting that FPTP can obscure deeper divisions beneath a broad-church façade. These parties then have to internally compromise leading to a consensus approach to politics. But what happens when one group has an outsized voice? What happens if one faction taps into something visceral? Well, Donald Trump.

The American two-party system shows the other side of the coin. Trump has essentially captured the Republican party and the bastion of FPTP and the two-party system has kept him in power and made him a dominant force in US and global politics. Once the centrists are outside the castle walls, they have to scale them in the same way the extremists did, meaning the extreme can became the mainstream and remain protected by the system. FPTP is a careless system that will protect whoever has the most influence which is great when the sensible people are in charge, and not so great otherwise.

So what does all of this mean for the UK? Reform UK are consistently topping the polls so they must have breached the castle walls. Right?

Well yes, and no. As I discovered last year when I was predicting the US election politics is a bit like a financial market. The same is true in the UK. Right now, Reform UK is a speculative stock — people are putting a lot of faith and value into it but the party has only 5 seats and has not realised any of its gains at a national level. Reform UK are dominating the UK conversation, but until voters go to the ballot box it is all speculation. It’s like Henry V standing at Agincourt and saying “we’ll win this” before the battle has begun. Until you beat the enemy, it’s all just speculation. A bet that could reap huge rewards for its investors, or a bubble that could pop at any moment.

Britain has never had an extremist government. The key word there being “had.” Popular sentiment, and a leader adept at gaming national media could see all of that change overnight. Then the system that once protected Britain against the extremists could end up protecting them. If that day comes, the same filter that once blocked extremism may end up locking it in.